|

11Then Jesus said, “There was a man who had two sons. 12The younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of the property that will belong to me.’ So he divided his property between them. 13A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and traveled to a distant country, and there he squandered his property in dissolute living. 14When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that country, and he began to be in need. 15So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed the pigs. 16He would gladly have filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating; and no one gave him anything. 17But when he came to himself he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger! 18I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against

|

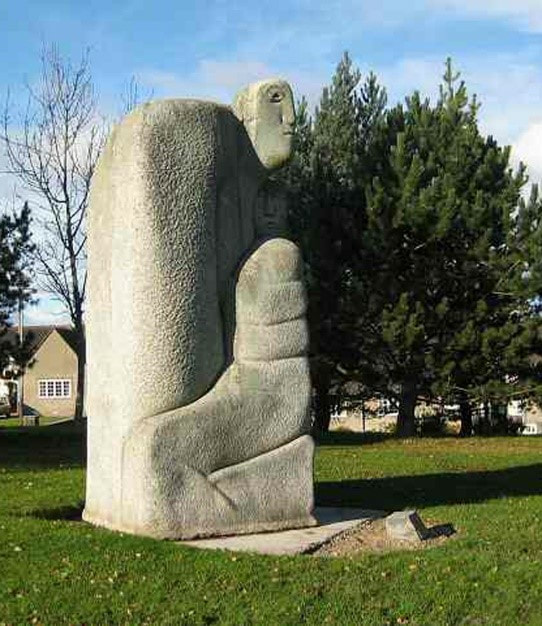

Le Breton, Jacques ; Gaudin, Jean. The Prodigal Son, 1933, from Art in the Christian Tradition

|

heaven and before you; 19I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.”’ 20So he set off and went to his father. But while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him. 21Then the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ 22But the father said to his slaves, ‘Quickly, bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. 23And get the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; 24for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!’ And they began to celebrate.

Eric Barreto, New Testament professor at Princeton Theological Seminary, writes

|

“When we are too close to the parables of Jesus, they tend to lose their edge. When we know the end of the story in our bones, parables no longer surprise us. When our interpretations boil parables down to bromides, Jesus no longer confronts us with hard truths. In short, when we find ourselves unsurprised by the parables, when we find ourselves confident of what a parable means, we can be sure we have missed Jesus’ provocative teaching.”

|

Such is often the case with the parable of the lost son, or as it is better known, the Prodigal Son. I think many of us who have been around church for many years hear that title and nod our heads knowingly. We could probably recite most of the story from memory. This is a parable that is often in our bones. And that’s the problem. We hear about a misdirected son who goes off to sow his wild oats, falls on hard times, and returns home with his tail between his legs where his loving father welcomes him home. And yes, that is definitely the gist of the story. But is there more? Like the other parables we have been digging into, are there other layers to this story that is so familiar? As we look at the historical context and first century Jewish practice, we find that there definitely are!

As there are many layers to this parable, so too are there many interpretations. These are very complex characters! And as we are so far removed from the culture of the first century, so too is any understanding we can have of these characters and how their actions would be interpreted. Scholars range in their view of both the 2 sons and the father, seeing their actions both positively and negatively. It seems the more you read about this parable, the more confusing it gets!

First of all, many of us are so familiar with the word “prodigal,” but do we really know what it means? So we turn to good old Webster: “spending money or resources freely and recklessly; wastefully extravagant.” That makes all the sense in the world when referring to the son in our story. But Webster gives a second definition: “having or giving something on a lavish scale.” In this wonderful story, we will find we have not one prodigal character, but 2 who are reckless, wasteful, and extravagant.

First there’s the younger son – a truly pathetic character! He appears shameless and self-centered, as he asks for his inheritance from his father. Robert Farrar Capon in his book, Kingdom, Grace and Judgement, writes:

As there are many layers to this parable, so too are there many interpretations. These are very complex characters! And as we are so far removed from the culture of the first century, so too is any understanding we can have of these characters and how their actions would be interpreted. Scholars range in their view of both the 2 sons and the father, seeing their actions both positively and negatively. It seems the more you read about this parable, the more confusing it gets!

First of all, many of us are so familiar with the word “prodigal,” but do we really know what it means? So we turn to good old Webster: “spending money or resources freely and recklessly; wastefully extravagant.” That makes all the sense in the world when referring to the son in our story. But Webster gives a second definition: “having or giving something on a lavish scale.” In this wonderful story, we will find we have not one prodigal character, but 2 who are reckless, wasteful, and extravagant.

First there’s the younger son – a truly pathetic character! He appears shameless and self-centered, as he asks for his inheritance from his father. Robert Farrar Capon in his book, Kingdom, Grace and Judgement, writes:

|

“The parable is an absolute festival of death, and the first death occurs right at the beginning of the story: the father, in effect, commits suicide… The younger son comes to his father and says, ‘Give me the portion of goods that falleth to me’… In other words, he tells his father to put his will into effect, to drop legally dead right on the spot. Obligingly enough, the father does just that: he gives the younger son his portion in cash, and to the elder brother, presumably, he gives the farm. Thus, just two sentences into the parable, Jesus has set up the following dynamics: he has given the first son a fat living, he has made the brother, for all the purposes of the parable yet to come, the head of the household; real paterfamilias out of business altogether” (p. 294).

|

|

Although first century laws are unclear on this kind of situation, it was at the very least disrespectful to his father to demand his inheritance, but at its worst, he was essentially saying to his father, “I wish you were dead.” He breaks ties with both his family and the community, who would also have seen his behavior as shameful. The older son’s behavior is just as shocking as he should have been horrified at the very suggestion, but he accepts his brother’s suggestion and evidently, willingly accepts his inheritance as well. Kenneth Bailey suggests that the older son’s silence and acceptance of his brother’s request implies that his relationship with his father is not what it should be. (We’ll talk more about the older son next week.) But this behavior is more than shocking. The ancient world condemned children for a lack of care or neglect of parents. In fact, neglect of parents was an imprisonable offense. Deuteronomy 21:18-21 states that rebellious sons were to be stoned!

Probably, though, the most shocking response is that of the father. The NRSV reports that the father “divided his property,” but the Greek is much more pointed and is better translated, “he divided his life [Greek bios] |

Luke the Cypriot, active 1583-1625. Parable of the Prodigal Son, detail, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN

|

between them.” The father goes against all expectations – social, legal, familial – and would have been seen as acting dishonorably by the community. Bruce Malina and Richard Rohrbaugh in their Social Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels point out that in giving into the son’s request, he alienates the entire village where nonconformity is always a threat to community stability. The expectation in these close-knit communities of the first century was that everyone played by the community’s economic rules. In breaking ties with his sons, dividing all his estate between them, he now becomes dependent upon the community for his own welfare. (p. 290) The father is now seen by the community as weak and impoverished, and brings shame upon himself.

To underline the seriousness of such an act, Kenneth Bailey, scholar on the Gospel of Luke, who spent much of his work within the Middle Eastern peasant culture and brings a very unique cultural perspective for these parables, writes,

To underline the seriousness of such an act, Kenneth Bailey, scholar on the Gospel of Luke, who spent much of his work within the Middle Eastern peasant culture and brings a very unique cultural perspective for these parables, writes,

|

For over fifteen years I have been asking people of all walks of life from Morocco to India and from Turkey to the Sudan about the implications of a son’s request for his inheritance while the father is still living. The answer has almost always been emphatically the same… the conversation runs as follows:

“Has anyone ever made such a request in your village?” “Never!” “Could anyone ever make such a request?” “Impossible!” “If anyone ever did, what would happen?” “His father would beat him, of course!” “Why?” “The request means—he wants his father to die!” (Kenneth Bailey, Poet and Peasant, p. 161-162) |

|

Rae, Ronald. Return of the Prodigal, 1983, from Art in the Christian Tradition

|

It was common practice for inheritance between multiple sons to be divided unevenly. The oldest son received a double share of the inheritance He usually received the inheritance as the estate, flocks, and belongings. Younger sons’ portions were customarily converted to cash. So the older son stayed home on the family farm to run it and the younger son takes his money and leaves.

But things get worse. First, he travels to a distant country – Gentile territory! Then he squanders his money on all sorts of unconscionable activities. When a famine hits the land, his impoverishment is only hastened. And finally, he finds work as a laborer, tending pigs for a Gentile. Pigs, of course, are considered unclean by Jewish law, and tending them would have been seen as sinking lower than low. Bailey writes, “Here the prodigal gradually descends into his own hell.” But the son is so destitute, so hungry, that he was willing to debase himself even further, willing to |

eat the food that the unclean pigs ate. Bailey goes on to explain that having spent all his inheritance, he “glues” himself to a citizen of that country. He writes,

|

This lad is known in the community as having arrived with money and thus is expected to have some self-respect left. The polite way a Middle Easterner gets rid of unwanted ‘hangers-on’ is to assign them a task he knows they will refuse. Anyone with food in a severe famine has a throng of petitioners at his door daily. However, the pride of the prodigal is not yet completely broken and, to the amazement of the listener/reader, the citizen’s attempt to get rid of the younger son fails. He accepts the job of a pig herder. (p. 170-171)

|

The concluding comment about the younger son’s experience is, “and no one gave him anything.” The Greek is better translated, “no one was giving to him,” meaning that he probably tried begging, but even that didn’t work.

It is here, in the pigpen, where the son comes face to face with the second death of the story. (Capon) The son is dying of hunger. But he also begins to come to terms with the fact that he is now dead as a son as well. He severed the relationship when he demanded the inheritance and left. He has lost all claim to his position of “son-ness,” and can only imagine returning as a hired hand. The family is broken, lost. He is now no longer a son.

It is here, in the pigpen, where the son comes face to face with the second death of the story. (Capon) The son is dying of hunger. But he also begins to come to terms with the fact that he is now dead as a son as well. He severed the relationship when he demanded the inheritance and left. He has lost all claim to his position of “son-ness,” and can only imagine returning as a hired hand. The family is broken, lost. He is now no longer a son.

|

But then Jesus uses this interesting phrase, “But when he came to himself…” No further explanation is offered, and it is left to the reader what this could mean. Does he claim his identity while realizing he no longer has any claim to “son-ship,” no longer deserving of his father’s graciousness? Does he realize that he has travelled far and needs to reclaim his own roots? Does he repent, choose to turn away from this corrupt lifestyle? Is he clever, and a bit crafty, knowing that his father will take him in again? Or is his return motivated primarily by his stomach (Malina and Rohrbaugh, p. 290)? In any event, he returns to his own land and to his father. He has no thoughts of returning as a “son.” Although the story doesn’t reveal anything, perhaps he realizes his family has been destroyed by his actions,

|

Forain, Jean Louis, 1852-1931. Prodigal Son, from Art in the Christian Tradition

|

and his relationship with his father and brother is ended. He is, in essence, dead to his family, yet he chooses to return in a new relationship, as a stranger, an alien, a hired hand.

But instead, he returns to a father who acts completely at odds with expectations. All this time, the father must have been standing at the edge of his property watching for him, because while the son is still far off, his father sees him, and recognizes him. Jesus tells us that the father is “filled with compassion.” Once again, as with the Samaritan, we have that wonderful Greek word, splanchnidzomai, compassion that comes from deep within one’s insides, gut-wrenching compassion. Then the father does something no self-respecting, dignified Middle Eastern man would ever be seen doing; he runs to his son. Malina and Rohrbaugh explain that hiking one’s robes to run would not only lack dignity, but it was inappropriate to expose one’s legs and would cause dishonor. But this loving, compassionate, crazy father doesn’t care, so great is the love he has for this son who has so deeply wronged him.

The father runs out to the son, embraces him, kisses him, then puts a robe and sandals on him, and gives him a ring. Acting not only out of compassion and joy, the father could be acting out of protection for his son. Having left the village under such disgraceful circumstances, breaking every custom and law, the villagers would have most likely have acted with a great deal of hostility, especially if they discover that he lost his share of the family property to non-Israelites. Families would be afraid their sons could get similar ideas (Malina and Rohrbaugh, p. 290).

The “best” robe would have been the robe worn by the father for ceremonial occasions and would have shown the community that the younger son is accepted as a member of the household. The sandals would have established the son as a member of the family, a free man in the household, and not a servant. The ring, however, is extraordinary. It would have probably been a signet ring which in that time would have been used as a way of sealing one’s identity on legal contracts, including borrowing money. This son who squandered everything is now given the family credit card! The fatted calf is killed and all the village is presumably invited to the feast to welcome home the son, and to proclaim to the community that this son is fully accepted back into the family, and should be likewise accepted back into the community. This creates some tension, however. Is the father giving away the older son’s property??? After all, he already gave away his estate when he divided the inheritance between the two sons! More on that next week…

This homecoming scene paints a joyful picture of the return of a beloved son which is unexpected and frankly, a little scandalous. This parable has always been known as the “Prodigal Son,” but perhaps is misnamed, and should instead be named the “Prodigal Father.” After all, it is the father who shows extravagance, wastefulness, and irresponsibility.

The picture of the father, however, reflects on the reality of God, who is also extravagant, wasteful, and even irresponsible in showing love for humanity. The entire Bible is one story after another of God’s grace raining down on humanity, and humanity’s failure or rejection of that grace. The first 11 chapters of Genesis show that very pattern. God creates out of love, and the man and woman reject that love. Although they are put out of the garden, they are allowed to live and have children, Cain and Abel. Cain kills Abel, is hated by others for his actions, but God acts by placing a mark of protection on him. As more and more people populate the earth, they become more and more sinful, so God sends a flood, but saves Noah and his family and places a rainbow in the sky that he will never flood the world again. The people once again, want to become like God and peer into heaven by building a tower. God confuses their language, but continues to act out of grace-filled love and calls Abraham and Sarah. The story continues with the up and down of God’s grace and human rebellion through Abraham's descendants, through Israel’s history of failing to care for the widow and orphan and ending in exile in Babylon. But God’s faithfulness and love never fails, as God sends Gabriel to a little town in Galilee, to Nazareth, to Mary who will bear God’s Son who will redeem the world. It’s pretty scandalous that God never gives up on humanity, but continues to shower love and forgiveness and grace on us.

The story of the Prodigals has often been called “the gospel within the gospel” because it so clearly and beautifully reflects God’s love in the face of rebellion, failure, and hopelessness. It is our story. Because it assures us that “nothing in all creation will separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus, our Lord” (Romans 8:35).

Reflection Questions

Please share your thoughts about this lesson and any of the discussion questions in the box below

But instead, he returns to a father who acts completely at odds with expectations. All this time, the father must have been standing at the edge of his property watching for him, because while the son is still far off, his father sees him, and recognizes him. Jesus tells us that the father is “filled with compassion.” Once again, as with the Samaritan, we have that wonderful Greek word, splanchnidzomai, compassion that comes from deep within one’s insides, gut-wrenching compassion. Then the father does something no self-respecting, dignified Middle Eastern man would ever be seen doing; he runs to his son. Malina and Rohrbaugh explain that hiking one’s robes to run would not only lack dignity, but it was inappropriate to expose one’s legs and would cause dishonor. But this loving, compassionate, crazy father doesn’t care, so great is the love he has for this son who has so deeply wronged him.

The father runs out to the son, embraces him, kisses him, then puts a robe and sandals on him, and gives him a ring. Acting not only out of compassion and joy, the father could be acting out of protection for his son. Having left the village under such disgraceful circumstances, breaking every custom and law, the villagers would have most likely have acted with a great deal of hostility, especially if they discover that he lost his share of the family property to non-Israelites. Families would be afraid their sons could get similar ideas (Malina and Rohrbaugh, p. 290).

The “best” robe would have been the robe worn by the father for ceremonial occasions and would have shown the community that the younger son is accepted as a member of the household. The sandals would have established the son as a member of the family, a free man in the household, and not a servant. The ring, however, is extraordinary. It would have probably been a signet ring which in that time would have been used as a way of sealing one’s identity on legal contracts, including borrowing money. This son who squandered everything is now given the family credit card! The fatted calf is killed and all the village is presumably invited to the feast to welcome home the son, and to proclaim to the community that this son is fully accepted back into the family, and should be likewise accepted back into the community. This creates some tension, however. Is the father giving away the older son’s property??? After all, he already gave away his estate when he divided the inheritance between the two sons! More on that next week…

This homecoming scene paints a joyful picture of the return of a beloved son which is unexpected and frankly, a little scandalous. This parable has always been known as the “Prodigal Son,” but perhaps is misnamed, and should instead be named the “Prodigal Father.” After all, it is the father who shows extravagance, wastefulness, and irresponsibility.

The picture of the father, however, reflects on the reality of God, who is also extravagant, wasteful, and even irresponsible in showing love for humanity. The entire Bible is one story after another of God’s grace raining down on humanity, and humanity’s failure or rejection of that grace. The first 11 chapters of Genesis show that very pattern. God creates out of love, and the man and woman reject that love. Although they are put out of the garden, they are allowed to live and have children, Cain and Abel. Cain kills Abel, is hated by others for his actions, but God acts by placing a mark of protection on him. As more and more people populate the earth, they become more and more sinful, so God sends a flood, but saves Noah and his family and places a rainbow in the sky that he will never flood the world again. The people once again, want to become like God and peer into heaven by building a tower. God confuses their language, but continues to act out of grace-filled love and calls Abraham and Sarah. The story continues with the up and down of God’s grace and human rebellion through Abraham's descendants, through Israel’s history of failing to care for the widow and orphan and ending in exile in Babylon. But God’s faithfulness and love never fails, as God sends Gabriel to a little town in Galilee, to Nazareth, to Mary who will bear God’s Son who will redeem the world. It’s pretty scandalous that God never gives up on humanity, but continues to shower love and forgiveness and grace on us.

The story of the Prodigals has often been called “the gospel within the gospel” because it so clearly and beautifully reflects God’s love in the face of rebellion, failure, and hopelessness. It is our story. Because it assures us that “nothing in all creation will separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus, our Lord” (Romans 8:35).

Reflection Questions

- What new revelations come to light for you in this story?

- What questions do you bring to this parable?

- How do we live out this grace for ourselves? How do we live it out in our congregations?

- Have you ever experienced grace as the younger son experiences being welcomed back into his Father’s arms? What did it feel like?

Please share your thoughts about this lesson and any of the discussion questions in the box below