|

25“Now his elder son was in the field; and when he came and approached the house, he heard music and dancing. 26He called one of the slaves and asked what was going on. 27He replied, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has got him back safe and sound.’ 28Then he became angry and refused to go in. His father came out and began to plead with him. 29But he answered his father, ‘Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. 30But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!’ 31Then the father said to him, ‘Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. 32But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.’”

|

Le Breton, Jacques ; Gaudin, Jean. The Prodigal Son, 1933, from Art in the Christian Tradition

|

It seems as if we should begin our study with the words, “Previously on a road in Galilee,” and begin with scenes from last week, because the story of the Lost Brother is a continuation of the story known as the Prodigal Son. If this were a piece of music, this could be seen as the second movement. Unfortunately, the story of the elder brother doesn’t get as much attention. I wonder if it’s because this is the part that may make us squirm a bit. This is a story of jealousy, bitterness, and a refusal to forgive, thus a refusal of grace.

But can’t we understand the older son’s position? It’s sibling rivalry like probably most parents (and siblings!) have encountered – “You love my sister/brother more than me!” But in this case, it probably does feel that way to the older son. Although he did, shockingly, accept the inheritance, when his father divided it between him and his brother, he presumably did everything right. He stayed and worked the farm, cared for the family, did what was expected of him. In other words, he followed all the rules. Unlike his younger brother who squandered everything and would be labeled shameful by the community as well as the reader, the older son would be most likely be a respected member of the community. But when the younger son who had acted irresponsibly and shamefully returns, the celebration begins. Jealousy is a powerful emotion!

The older son begins the story out in the fields and presumably has no idea what was going on, so when he returns to the house, he needs to ask the servants. In Greek, the verb “asked” in verse 26 is in the imperfect tense, which in Greek implies that the son “kept asking him.” This probably implies that he asked a number of questions, not only who was partying, but once he discovered his brother had returned, whether he had come back wealthy or poor. At this point he presumably does not know that he lost everything. The younger brother’s behavior in leaving was reason enough to feel slighted. He will find out that he had lost everything, but for now, the emphasis is on remaining and working rather than squandering the fortune. The older son, we are told, becomes angry and refuses to go into the party. Now both the sons have been separated from the father by distance. Culpepper states that this physical separation signifies alienation.

But can’t we understand the older son’s position? It’s sibling rivalry like probably most parents (and siblings!) have encountered – “You love my sister/brother more than me!” But in this case, it probably does feel that way to the older son. Although he did, shockingly, accept the inheritance, when his father divided it between him and his brother, he presumably did everything right. He stayed and worked the farm, cared for the family, did what was expected of him. In other words, he followed all the rules. Unlike his younger brother who squandered everything and would be labeled shameful by the community as well as the reader, the older son would be most likely be a respected member of the community. But when the younger son who had acted irresponsibly and shamefully returns, the celebration begins. Jealousy is a powerful emotion!

The older son begins the story out in the fields and presumably has no idea what was going on, so when he returns to the house, he needs to ask the servants. In Greek, the verb “asked” in verse 26 is in the imperfect tense, which in Greek implies that the son “kept asking him.” This probably implies that he asked a number of questions, not only who was partying, but once he discovered his brother had returned, whether he had come back wealthy or poor. At this point he presumably does not know that he lost everything. The younger brother’s behavior in leaving was reason enough to feel slighted. He will find out that he had lost everything, but for now, the emphasis is on remaining and working rather than squandering the fortune. The older son, we are told, becomes angry and refuses to go into the party. Now both the sons have been separated from the father by distance. Culpepper states that this physical separation signifies alienation.

|

Verse 28 seems to bring us to the dramatic climax of the parable. The father comes out to his son. Bailey explains that in Middle Eastern culture, the son’s actions are extremely insulting. He is treating his father with disdain, something that would never have been accepted in that first century culture. Even the father “coming out” to plead with his son would have been seen as shameful – fathers do not plead with their young sons.

|

Artist unknown

|

Sons are expected to respect and honor their elders. His refusal to join the celebration is also a huge affront. The culture would expect him, as the oldest son, to be a part of the celebration. Again, he is dishonoring his father, not behaving as a son should.

As the relationship with the younger son is now restored, the relationship between the father and the older son is broken. The older son refers to their relationship no longer as family, but now as a master and a slave. He is essentially saying, I have worked – where are my wages, reflecting the atmosphere of a labor dispute over wages rather than that of family. Ibrähīm Saʿīd in his commentary on Luke writes:

|

This is the spirit of the Pharisees by which he (the older son) enters into the ranks of the “ninety-nine who need no repentance”; thus even if he has never disobeyed his father’s commandments, yet he has with this action broken the commandment of love. |

Saʿīd then compares the older son’s action to the younger son’s:

|

The difference between him and his younger brother was that the younger brother was estranged and rebellious while absent from the house, but the older son was estranged and rebellious in his heart while he was in the house. The estrangement and rebellion of the younger son were evident in his surrender to his passions and in his request to leave his father’s house. The estrangement and rebellion of the older son were evident in his anger and his refusal to enter the house. |

So the older son accuses his father of favoritism saying, “You have never given me even a young goat.” In Greek, word order is important, and is perhaps better translated, “To me you have never given a kid.” The first words in a sentence are considered weighted, more important, therefore it’s the older son’s egocentrism that comes out strongly.

In addition to describing the relationship with his father as that of a slave, he goes on to further distance himself from the family with the phrase, “this son of yours.” This phrase is then echoed in the words of the father, pleading with the older son when he says in verse 32, “we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life…” The father is attempting to restore the relationship, to reunite the family.

And so the parable ends on an ominous note. It’s harsh. And it doesn’t end in a “happily ever after” manner. In fact, we really don’t know how the story ends. Does the older son have a change of heart and join the celebration, or does he walk away bitterly? Wouldn’t we feel better if there was a verse 33 that read, as Kenneth Bailey writes in his book, Poet and Peasant: “And he came and entered the house and joined in the music and dancing and he began to make merry. And the two sons were reconciled to their father.” But it doesn’t.

Jesus’ parables are relatable. They are about common things, familiar emotions and situations. And although the culture of the first century is quite different, and it is helpful to get our heads around its customs a bit, even in our own contemporary world, we can relate to these characters. So the question must be considered: Who am I in this story?

In addition to describing the relationship with his father as that of a slave, he goes on to further distance himself from the family with the phrase, “this son of yours.” This phrase is then echoed in the words of the father, pleading with the older son when he says in verse 32, “we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life…” The father is attempting to restore the relationship, to reunite the family.

And so the parable ends on an ominous note. It’s harsh. And it doesn’t end in a “happily ever after” manner. In fact, we really don’t know how the story ends. Does the older son have a change of heart and join the celebration, or does he walk away bitterly? Wouldn’t we feel better if there was a verse 33 that read, as Kenneth Bailey writes in his book, Poet and Peasant: “And he came and entered the house and joined in the music and dancing and he began to make merry. And the two sons were reconciled to their father.” But it doesn’t.

Jesus’ parables are relatable. They are about common things, familiar emotions and situations. And although the culture of the first century is quite different, and it is helpful to get our heads around its customs a bit, even in our own contemporary world, we can relate to these characters. So the question must be considered: Who am I in this story?

|

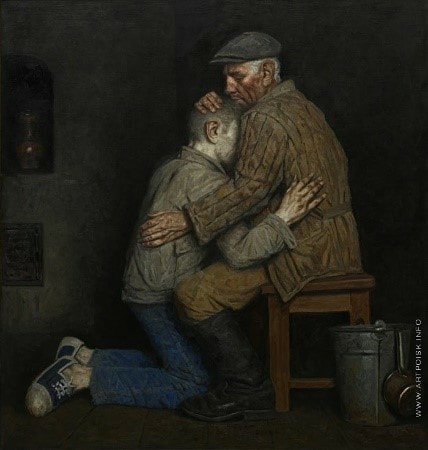

The Prodigal Son. Painting by Geliy Korzhev

|

Do we see ourselves as the lost younger son who runs away and squanders the father’s love, who turns his back on the relationship the father has given to him throughout his life? Or do we see ourselves as the older son who has remained faithful his entire life, done everything expected of him, yet bitter when others appear who have not necessarily “earned” the dancing and merry-making of a big party? Or do we see ourselves as the loving parent who would never turn his or her back on their child, arms open wide in welcome and love? The answer may simply be, “Yes!” There may be times we see ourselves in each of these characters. And that is the genius and beauty of the parables! They engage us in different ways at different times of our lives.

|

But there’s still that ending! It really does make us squirm. Does the older son finally go into the celebration, thus accepting the return and the grace that is heaped upon his younger brother? Or does he remain outside in the dark, hearing the music and laughter and clinking plates inside? The idea of sin can be defined in so many ways, but the most powerful, and probably the most meaningful is to define it as a separation from God. Sin does not refer to the things we do or fail to do. It is a state, a condition of our rebelliousness, brokenness, and ultimately our hopelessness. The condition of sin can be thought of as building a wall, brick by brick, between ourselves and God. When we build that wall, we focus more and more on ourselves, and in building that wall, we also wall ourselves off from others – from community, from the joys and hope, from the needs we can fulfill. And we wall ourselves off from our prodigal brother and prodigal father until all we see are our own disappointments, our own bitterness, and the failures of our own lives. We are as egocentric as the older son who begins his rant, “To me you never even gave a kid!” And that’s all we can see.

The father, however, lovingly comes to us, pleads with us, begs us to join the celebration, to rejoice, to feast that love and grace and forgiveness abound. So will the older son be reconciled to his father and his brother? Will he join the celebration? Will he remain locked away behind the wall he has built, or will he allow the father to tear it down so that he can see grace and love and forgiveness in action? We’ll never know.

R. Alan Culpepper, in his New Interpreter’s commentary on Luke writes, “Did he go in and welcome his brother home, or did he stay outside pouting and feeling wronged? The parable ends there because that is the decision each of us must make. If we go in, we accept grace as the Father’s rule for life in the family.”

And so we come to the end of chapter 15 of Luke’s gospel – 3 parables told in the face of the Pharisees and the scribes having a hissy fit that Jesus was eating with sinners and tax collectors. And these parables make Jesus’ point powerfully. As Culpepper puts it:

The father, however, lovingly comes to us, pleads with us, begs us to join the celebration, to rejoice, to feast that love and grace and forgiveness abound. So will the older son be reconciled to his father and his brother? Will he join the celebration? Will he remain locked away behind the wall he has built, or will he allow the father to tear it down so that he can see grace and love and forgiveness in action? We’ll never know.

R. Alan Culpepper, in his New Interpreter’s commentary on Luke writes, “Did he go in and welcome his brother home, or did he stay outside pouting and feeling wronged? The parable ends there because that is the decision each of us must make. If we go in, we accept grace as the Father’s rule for life in the family.”

And so we come to the end of chapter 15 of Luke’s gospel – 3 parables told in the face of the Pharisees and the scribes having a hissy fit that Jesus was eating with sinners and tax collectors. And these parables make Jesus’ point powerfully. As Culpepper puts it:

|

The three parables in this chapter [the lost sheep, lost coin, and prodigal son] make their point effectively. The position of the Pharisees and scribes who grumbled because Jesus ate with tax collectors and sinners has been unmasked as the self-serving indignation of the elder brother who denied his relationship both to his father and to his brother by his refusal to join in the celebration. In the world of the parable, one cannot be a son without also being a brother.

|

Did the Pharisees and scribes have a change of heart? We don’t know if any of them actually did. But Jesus still was betrayed and arrested and put to death. Unconditional love is hard to understand – especially when the recipients seem undeserving. It’s unfair! Indeed! God is unfair!!! And thank God for that!

Reflection Questions

Please share your thoughts about this lesson and any of the discussion questions in the box below?

Reflection Questions

- What new insights, thoughts, questions do you have about this parable?

- Now that we've looked at the whole story, who do you most relate to? Who you not relate to?

- What are the implications for our congregations if the God we follow is reckless with love? What are the implications for us?

Please share your thoughts about this lesson and any of the discussion questions in the box below?